Städtische Kunsthalle Mannheim 1989

The Formation of Emptiness

by Sarit Shapira

“This web of time—the strands of which approach one another, bifurcate, intersect or ignore each other through the centuries—embrace every possibility. We do not exist in most of them. In some you exist and not I, while in others I do, and you do not, and in yet others both of us exist.”

—Jorge Luis Borges, The Garden of Forking Paths (1)

In Michael Gitlin’s drawing works exists not only as a preparatory sketches for sculpture, but also as an autonomous medium, developed throughout the artist’s activity. The drawings share many characteristics with his sculptures, especially his wall sculptures. Many of these are made up of fragments of boards, planks, or logs of wood, their connection to each other appearing temporary and somewhat shattered. The drawings are also constructed of lines that are often broken and disjointed; the contacts between them flimsy, fragile or even absent.

One of the remarkable features of the sculptures is the tension between the seeming fragility of the actual physical connections, the vulnerability of the sculptural matter, and the assuredness, complexity and energy of the sculpture’s movement. Tension exists in Gitlin’s drawings between the details tenuously connected to each other, and their organization into a sweeping, all encompassing movement. In drawing as in sculpture, Gitlin uses broad forms that end in sharp edges which project into space like arrows or missiles. Much use is made of serpentine motions, that revolve around their own axis and spin off in different directions. Drawing, by its very nature a medium insubordinate to the physical laws of material, increases the potential of freedom and the complexity of movement in space by fragmentary indices lacking solid interconnections.

Though the fractured lines on paper are basically abstract, their movement causes the spectator bodily sensations; bursting forth, withdrawing, twisting in serpentine movements, slight risings resonant with moments of awakening, upward stretching and a sudden plummet. The erased marks concretize minute body gestures; the lines painted over are like movements that have receded into the depth of space. The thick lines are strong, rhythmical, reflecting almost violent body movements. The drawings can also be read as traces of the movement of a dancer who organizes motion in a given space. The choreographic character and the concretization of body language also exist in Gitlin’s sculpture, and for this, too, Stephen Westfall named it “Humanizing Sculpture.” Referring to the sculpture “Equilibrium” (1980) Westfall has written: “It is the crucifixion as an abstract choreography, a sculptural equivalent of Newman’s ‘Fourteen Stations.’” In a more general way he would characterize Gitlin’s work as “Formal abstract theatre that integrates the viewer into the performance.” (2)

In his drawings, Gitlin uses both black and colored lines as a constructive, direction-generating element. They appear as strips dense with pigment, bordered by a stained even granular edge. The lines (the constructive components) are thus softened into more pictorial tissues. This blurring of distinction between drawing and painting’s language is especially remarkable when white lines cover up dark ones. This creates colorful tones, nuances of pictorial language, and also integrates the lines with the white area of the empty paper around them. Because of the tactility of the white lines they are felt to have greater material presence than the empty paper, the last being perceived not so much as “material” than as “space”.

In his sculptures Gitlin uses color (very often green) and thus inserts a pictorial factor into what is basically a constructive medium. The surface of the sculpture, its bare and bruised tissue (the sculpture’s “flesh”) often covered or saturated with color is also conceived in painterly terms. The artist also contrasts the bare wood which gives a feeling of warmth associated with natural, organic matter, with the warmth of colorful matter associated with an artificial pictorial discipline.

The sculptures use the flat wall as a starting point from which they emerge into the concrete space of the room. In the drawings as well, the flat plane serves as background and starting point for the drawing activity. The exposure of the empty paper around and beneath the lines emphasizes the frontal plane of the drawing page as an environment and scene of action. But, similar to the components which make up the sculpture, the drawn lines intrude into the space in front of them (the concrete space of the room) and into that space which exists behind the plane of the paper. “One receives the impression,” Christine Tacke writes, “that the lines are trying to break away from the flat surface of the paper and move out into space. The lines at the front of the visual field shift into the background, from which other lines emerge and thrust themselves into the foreground.” (3) The lines turning into the space of the drawing, out of this space and to the back of it (an illusional turn) break through and “split” the paper plane, and to some extent also the wall plane adjacent to the paper. (4)

The lines moving from and into the space at right angles or in curves seem to be thick beams which move and give structure to a deep three-dimensional space. The changing and variation of their thickness and the density of the pigments in them render the lines oval and full. The longer, more meditative one’s dialogue with Gitlin’s drawings becomes, the more one perceives every mark both as a line in two-dimensional space and as a “body” present in a three-dimensional one. Many flat lines slant and turn into thicker and denser ones. The vibrations sensed from seeing the lines at first two-dimensionally, then as three-dimensional “bodies” become intensified at those junctions where the lines break and unite.

Intimate dialogue with the drawings reveals a “minor” activity taking place. Faint semicircular movements are found near the breadth of the lines. Following these “minor” movements, and experiencing the encounter between them and the more prominent lines, are among the fascinating adventures awaiting the viewer.

When the lines “fold,” break/connect at sharp angles, the spaces between them appear as triangular recesses; on one side of the serpentine lines, convex spaces are created, whereas “niches,” and concave spaces are created on the other. Through drawing Gitlin concretizes the empty space of the paper as voluminous and “full.” However, the lines in the drawings are often out suddenly, their momentum abruptly severed. Facing these ruptures it seems that the strong, energetic lines pierce the empty space as spears or harpoons.

The drawing defines the space around it not only as having volume, but also as having the characteristics of dense matter. Characteristically, the dark lines in Gitlin’s drawing and the way they are articulated give depth, material character and light to the empty space of the paper.

In his sculpture Gitlin also makes use of the empty space contained in nest-like compositions or forms resembling peels. These serve as a chassis, as protective covers, or as “negative forms” that “cast” the empty space in their pattern, and thus assign it form and territorial boundaries. (5) In sculpture and drawing alike, the forms remain fragmented and open, and the flow of space contained by them and enveloping them is thus emphasized.

Every form in Gitlin’s work has a “liminal” status, a sort of hybrid identity. It is separated from, but also perceived as akin to the space outside its boundaries. Conceptually, the identity of the form is defined by its limits. As previously mentioned, the drawings have no autonomous content, colorfulness, or tactility. In other words, they do not have “inwardness” and immanence a priori ascribed to them. The forms exist and are so defined as an outcome of their limits, and for this they can be characterized as having “liminal” identity.

The forms in the drawings containing empty space reflect other forms of similar character beneath them, the last reflecting further fragments and linear structures, and so on. This organization momentarily appears as fractions of transparent plates cast one on top of the other. The form is transparent so that through it other transparent structures will be uncovered, and so forth in a continuous and open process.

Every form is “transparent” to its adjacent forms, directed towards them in an additional way: Most of the forms expand into an open space on the page or unite with additional lines which move forward and then “fold” across other lines’ movements. The spectator’s eye is invited to move from one crossing point of the lines toward another and what was previously perceived by the eye as the limits of a certain form is then perceived only as part of, or in relation to, the limits of a new additional form. The lingering of the spectator’s eye on several “junctions” of the lines’ movements is that which practically creates the form’s limits. The departure of the spectator’s eye from one of these form’s “junctions” and its movement toward another meeting point immediately gives birth to new linear structures.

The linear structures do not have a stable, autonomous status. Being dependent on the spectator’s ever-changing viewpoint they are preceived as relative and momentary options, as contours existing in a liminal status. Possible definitions of one form are changed (sometimes “absorbed”) into the borders of another. These exchanges intensify as the lines often disassemble, break and splinter, while energetically and sweepingly moving in the shape of a wave or even a whirlpool. The more the motion and acceleration of the splintered lines are increased, the more difficult it becomes for the spectator to identify forms, even temporary ones. The lines can be seen as retaining traces or echoes of the shapes in space.

In many of the drawings the movement encircles the center of the paper. The lines often assume a three-dimensional serpentine form, the edges of which rotate and turn toward the heart of the space. In addition to these there are also lines that move in a horizontal or vertical motion; but these likewise refer to a central axis (straight or diagonal) of the drawing paper. However, this linear movement does not pass precisely through the central axis of the drawing but in deviation from it. It is not derived from it, but only relates to it as if marking its “empty“ presence.

This movement can also be simultaneously perceived as a seismograph of centrifugal motions, swept from the center to the margins of the paper. This energetic motion should not be preceived as deriving from an immanent center or as realizing and “filling” that center. Rather, the dark and energetic movement around the drawing’s center emphasizes and concretizes this empty center as an energetic core of the plane and as a focal point in a deep space.

The empty center of the work—the term “center” understood conceptually, namely paralleling “foundation,” “principal,” “substructure,” “heart,” “skeleton,” “main-coordinates,” etc.—is then of a liminal status: its intensive presence is dependent on a linear movement within the limits of the empty center, intermittently exploding into the open space.

The potential of dispersal of a line’s movement arouses the sensation that the drawing’s activity will shift and continue from the original page where it appears, on to another page—on to an additional space, to “load” its empty presence—in a momentary and liminal way, and in it to create forms.

Notes

1. Jorge Luis Borges, “The Garden of Forking Paths,” in Ficciones, Grove Press Inc., New York 1962, p. 100.

2. Stephen Westfall, “Humanizing Sculpture,” in Michael Gitlin, Cat. Kunstraum München, April–May 1986, pp. 16, 17.

3. Christine Tacke, “Michael Gitlin in Munich,” in Michael Gitlin, Cat. Kunstraum München, April–May 1986, p. 10.

4. In this context it might be interesting to mention the piece “Broken Infinity” that Michael Gitlin made in Autumn 1988 at the Bonner Kunstverein. In this installation, linear beams made of wood broke through walls that stood between them (see: Michael Gitlin, Broken Infinity 1986–1988, Cat. Bonner Kunstverein 29. 9.-16.11.1988).

5. Concerning the meaning of “negative forms” in Post-modernist context see: Rosalind Krauss, “The Originality of the Avant-Garde: A Postmodernist Repetition,” October No. 18 (Fall 1981) pp. 47–66.

Kernel and Shell:

The Principle of Dualism in the Sculpture of Michael Gitlin

by Jochen Kronjager

Michael Gitlin’s sculpture “Equilibrium” (1980) adumbrates the paradigmatic themes that have determined the direction of his work throughout the last decade: the relationship of the inner core of a material to its outer surface, and its substantial and energetic relationship to space. The sculpture consisted of a massive column of wood, three-meters high and approximately 50 cm square, painted black, from which four sections had been cut away, down to about 50 cm above the base. At the front and back the whole surface had been cut away, like a board; the cuts at the side, on the other hand, had the appearance of narrow beams. Thus the centrepiece of the installation at I.C.C. Antwerp was a square wooden column on a black base, with the four sliced sections from the original object suspended on the walls of the room. The black painted surfaces of the sections faced the wall, while their cut inner surfaces engaged in a dialogue with the column.

This installation provides a key to the almost mathematical logic of Gitlin’s works. Their core points to their outer shell, and vice versa, in a complex relationship between part and whole which is far from easy to decipher. Gitlin believes in the value of difficulty, like that which Rosalind E. Krauss identifies in David Smith’s work. Illusion in sculpture is concerned with its resistance to possession in the way that we can possess other objects: “The illusion in sculpture turns on the question of possession itself: either actual physical possession or, in a more sublimated form, intellectual possession—the viewer’s ability to comprehend.“ (1)

It is necessary to comprehend how the different systems which Gitlin uses combine reticence and dynamism, meditation and disquiet, form and formless-ness; to comprehend how Gitlin yields to the age-old principle of positive versus negative, warm versus cold, colour versus non-colour, ying versus yang. In short, to realize that his work is based on the principle of dualism, a specifically human principle which is at one and the same time simple and difficult, a principle which has literally to be grasped and experienced.

This is confirmed by the works that followed “Equilibrium.” “Sentinel” (1981/82), “Green Counterpoint,” and “Push and Pull” (both made in 1983) are sculptures in which there is a dialectical correspondence between that which has been taken away and that which remains. In the cycle of works shown at the Emmerich-Baumann Gallery in Zurich in 1985, Gitlin began to explore the opposing extremes: here, what one may call the “shell” is dominant. “Open Enclosure,” “Encroached Arc,” and “Space Link” (all made in 1984) are fragile, open, spatially demanding constructions which are formed around the bulk of what they might contain. Their frail, vulnerable appearance is reminiscent of the discarded peel of a fruit.

These sculptures were followed in turn by a series of constructions using wooden slats, which again appear to envelop and protect something within, some invisible spatial or mental content. The series includes bot the “Shelter” constructions which Gitlin began making in 1985 (cf. ill. 10, but also ///. 21) and the “accumulations” such as “Accumulation Inside-Out” and “Accumulated Headpiece,” both of which were also made in 1985.

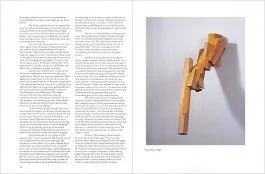

With the exception of “Equilibrium,” all these works are wall pieces which derive their sculptural disposition from the fact that they have a certain background, a foil. They throw a shadow which is an integral part of the work; it fills out and complements the plastic contours of the sculpture. These works unfold their potential on the wall, and at the same time the wall determines their character as reliefs. Gitlin at this stage is essentially a relief artist—even where his works extend into space, they have the character of reliefs.

This is confirmed by “Nostalgia,” a sculptural ensemble on which Gitlin worked from 1980 to 1986, the year in which it was first shown at the Kunstforum in Munich. The basis of this work is a block of six wooden beams, painted blue, sections of which have been sawn off and laid out in the centre of the room. Thus parts of the sawn-off sections are blue, while the others are the colour of the original wood, and this contrast between colour and non-colour lends the ensemble a graphic, two-dimensional appearance. In addition to this graphic effect the work has an astonishingly vital life of its own: the sawn-off sections are grouped around the original six-part block and create the appearance of a multifaceted pyramid. The two-dimensional aspect of the whole reminds one of Picasso’s early Cubist portraits.

This graphic approach is retained in Gitlin’s next set of works. “Broken Infinity“—conceived in 1986 and shown at the Kunstverein in Bonn in 1988—consists of a horizontal figure eight, the mathematical symbol for infinity, made of eight wooden beams running through three rooms and breaking through two of the walls. The work is essentially a drawing in space, similar to the wool sculptures of Fred Sandback. But unlike the latter works, it cannot be experienced at a single glance: “As a material whole, ‘Broken Infinity’ is not perceptible in a physical sense. To comprehend the structure it is necessary to ‘recollect‘ the parts in memory as one goes from room to room. The walls, as boundaries to be penetrated, indicate the point at which the visible and the invisible, seeing and feeling, come together to become perceptual correlations of the finite and infinite, of matter and spirit.” (2)

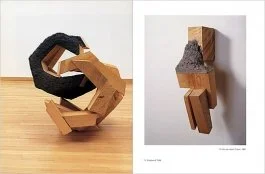

Since 1986 Gitlin’s concern with space has taken an increasingly aggressive form: the reliefs extend outwards, and their contours are sharp-edged. The projecting sections are painted in spatially demanding colours such as the green of “Your Head or Mine” and “Fragile Sanctuary” (1986). At the same time Gitlin has also been engaged in making a series of block shapes, also with sharp edges, which simultaneously usurp and suggest space. These groups of wooden blocks are connected or covered with a thick layer of coloured plaster mixed with sawdust. Examples of this latter group of works are to be seen in “Resolution” (ill. 1), “Grey Cast” (ill. 8), “Sculptural Concerns II” (ill. 11), “Wrap” and “Unembraceable” (ill. 12), and “Accumulated Matter” (ill. 16).

Gitlin uses colour in different ways: as a signal (in the way described above), as part of the “skin” of a sculpture (especially in his earlier work) (3), and as the “cement” which binds together the different parts of a sculpture (as in the groups of wooden blocks and the examples below). Retaining these categories in order to preserve his artistic freedom, Gitlin does not assign an a priori meaning to colour: in his work it is an abstract quantity, the part of the work which is added to the raw material, as an element of the “skin” or the bonding agent. As an element in the form of the sculpture it serves to create a contrast: the coloured sections of Gitlin’s works often have an amorphous appearance, standing in opposition to the massive angular outlines of the wood and enhancing its structured form. He has a marked preference for green and blue: light colours whose spatial effect emphasizes the plastic quality of the works. This effect is cancelled by the use of black, which nullifies contour and space. Black has a diffuse heaviness, a sombre inflexibility which contrasts with the “living” untreated wood and hence also underlines the plasticity of the object. (4)

Gitlin’s talent has several facets: in addition to the conglomerations of large wooden blocks laid out on the floor he has made numerous wall sculptures, using wooden slats or small blocks, which project out into space, almost like medieval drawbridges. These structures too are bonded together by layers of colour mixed with plaster and sawdust. Hung at eye level, they have a highly individual, autonomous plasticity which holds the viewer at a distance and invites him to walk round them and inspect them from all sides. A further, highly important aspect of these works is the implication that, like the conglomerations of wooden blocks discussed above, they should be seen from below; their structure should hence be appreciated from a singularly unusual perspective. (See, for example, “Acid Flow” (ill. 9), “No Beneficiaries” (ill. 18), “Blue Waterfall” (ill. 20), and “Structured Flow” (ill. 22).)

A concentration of the wooden elements can be seen in Gitlin’s latest works. In the wall sculpture “Improvised Shelter” (ill. 23) and the floor sculptures “Pending Resolution” (ill. 7) and “Double Shield” (ill. 19), Gitlin piles up thick, heavy boards into spatially demanding assemblies which ultimately retain the character of reliefs: as the title of the sculpture “Off the Wall” (ill. 25) suggests, they have, as it were, climbed down off the wall onto the floor. The sculptural mass is defined by the core which is carved out of it, by, in Gitlin’s case, that which surrounds or encircles him. This is confirmed by the structure of one of his most recent works, “Displaced” (ill. 15), made in 1988, which appears to take up and develop the shell-like construction “Space Link” (1984). Summing up, it is possible to say that (like “Nostalgia”) “Pending Resolution,” “Double Shield,” “Off the Wall,” and “Displaced” create a uniquely plastic spatial effect; in the last instance, however—and one can physically experience this by walking round them—they manifest themselves as layers, curves, or facets in space.

Gitlin is a highly gifted artist in the media of drawing and relief sculpture. Everything which leaves the wall remains a part of the wall’s precondition: the result is a set of formulations for which the ground is truly prepared in the wall sculptures. The artistic intention of Michael Gitlin to address both thought and feeling—or, as Yona Fischer wrote in 1977, to create a basis between conception and perception (5)—can only really be grasped in the context of his work as a whole: the series of wall reliefs, the floor sculptures and the cycles of drawings, which are orientated towards the sculptural works. One aspect of his work leads to another, and it is only from the sum of the parts that a convincing whole results.