Michael Gitlin: 16 Works

THE LACK OF THE WHOLE

by Drorit Gur Arie

Michael Gitlin moved to New York in 1970. American Modernism, which surrounded him at the time with its different and profoundly conflicting ideological and aesthetic strands, is the reference point for the emergence of his art. He acknowledges a great debt to Abstract Expressionism, and in particular to Action Painting’s sense of unrestrained physical energy, Gitlin drew his work’s fundamental conceptual vocabulary from the Post-Minimalist moment of mid- and late-70s New York.

A group of works by Gitlin, 4X8 Series 1974/75, reflects a gradual transition from painting and two-dimensionality to sculpture and three-dimensionality, and signals Gitlin’s nearly total reliance on the architectonic space, since the wall and the floor form integral parts of the work. The works function as large black drawings on the wall’s “white paper” and demonstrate an ambivalence which is typical of all of Gitlin’s work—that constant state of in-betweenness: between tearing and splicing, between white paper and wall, between the linear and the lumpy, between the sensory and the conceptual.

4X8 Series #3, 1974/75

One of the works in this series has been reconstructed by Gitlin for the current exhibition, and greets the viewer upon entering the museum’s space. Its two parts are perpendicular to each other—one vertical and attached to the wall, the other lying on the floor. This arrangement makes it difficult to interpret the piece in terms of traditional modernist sculpture that is meant to be walked around, so the work remains somewhere between drawing and sculpture. It is evident that the two parts come from a single mother-unit, a sheet of plywood in a common industrial format, whose splitting was done with an axe, creating tension between the installation’s stillness and quietness and the violence of its motives and its manner of production. Like the other works in the series, which seem to “illustrate” the performative potential of the movement between “standing up” and “lying down”, it brings to mind a series of painted plywood objects made by Robert Morris in 1964.

At the same time, it also hints at Gitlin’s expressive-calculated disposition: the axe replaces the brush of Abstract Expressionism but without the abstraction of the original, since the two parts of the “form” are not a translation or a substitute for two human figures, but rather derivations from a standard form, from the contact with the material and from the deliberate action of force+tool.

Like other works by Gitlin from the 70s, 4x8 borrows its uniform and industrial basic unit from Minimalism, but the final work remains open and unfinished; it is composed of open parts that emphasize the space created inside the work, not only around it. The Gitlin object opens itself up and thus reflects a different structurality than the one underpinning the influential floor and wall works of Carl Andre or Donald Judd—which, although they were created from repeated modular units, always highlighted the wholeness of the complete work, the fact that nothing broke the gestalt it created. Gitlin, as already mentioned, not only breaks and divides the basic units but also exposes the process and the action, whose importance is fundamental to the final work.

The range of Gitlin’s actions in those years included cutting, displacement and marking, which severed the artistic image from the context of cultural conventions in order to turn it into an index—a sign that incorporates the tangible conditions and procedures of its creation and is rooted in the structure of language rather than in its semantic layers. Focusing on the material working procedures returned the artist’s body and choreography to the forefront of the practice, the presence of the acting body in the work process being the individual equivalent of the “universal” quality of the works themselves. In other words, by emphasizing the subjective action within a well-organized system, the artist creates a bridge between himself and the work and between himself, the work and the viewer. In Gitlin, exposing the sum of the actions that have created the work expands the work’s very space, which now also incorporates us: individuals who reconstruct the process in retrospect in real space and time.

Broken Infinity installation view

Broken Infinity installation view

BROKEN INFINITY

by Drorit Gur Arie

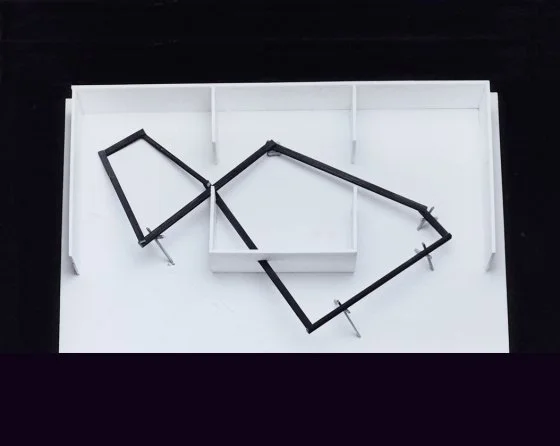

Spirals, arcs and supporting beams herald a constructive shift in Gitlin’s syntax in the 80s. His works become more open and trace a movement between potential building and actual collapse, this unsteadiness only increasing their dynamism in the space. The work Broken Infinity, designed as a model in 1986 and executed in a slightly different form in Kunstverein Bonn in 1988, is a natural consequence of this move. The work, which extended across three rooms and further expanded from them into the space, is shown at the current exhibition.

It is important to stress: it is not a “reconstructed work”, but a work that has been redesigned especially for the specific space of the Petach Tikva Museum of Art. The work’s centrality in the space stems not only from its size (this time a specially-adapted room has been built for it), but also from its importance as a key work in Gitlin’s oeuvre—a kind of bridge between the group of works described above and those that represent a newer practice, between the conceptual-formal concerns of the 70s and the conceptual-poetic opening that characterizes the amorphous works made of soft materials of the last years.

This interface has been identified by Annelie Pohlen, who finds in Broken Infinity some conceptual paradoxes that extend from the work’s title to its concrete experience. 67 meters of massive wooden beams painted green create a winding yet angular path that spreads across a white room, penetrates the architectonic crust and wounds it. The beams are supported by wooden tripods, which raise them to varying heights, creating a kind of broken Mobius ring, like the mathematical sign for infinity (∞). However, the conversion of a linguistic sign and of an abstract (mathematical, philosophical) concept into the very final and physical entity of the sculpture is in and of itself a conceptual rupture, like a botched transfiguration, or a failed attempt by infinity to come down to earth. “The attempt to give physical form to the logical link between the Unimaginable, on the one hand, and everyday experience, of fracture, on the other, […].

The struggle to represent that which is, in the end, unrepresentable determines the basis for the debate on sculpture as being a medium inherently aesthetic and at the same time a means for intellectually questioning a reality in need of definition,” observes Pohlen. Broken Infinity thus embodies the rupture of consciousness summoned by the concrete situation in the space. Sculpture expresses a movement that starts with an idea or a concept, passes through the hand to the sketch, the drawing and the design, and is consolidated in the material through a series of successive actions of breaking and building. For the viewer, the only way to rebuild the sign, the concept, is to reconstruct it by mentally walking backwards, pressing rewind and thus re-stitching together the pieces of the fractured physical experience.

Broken Infinity plan

Gitlin’s suggestion to include in the exhibition a plan with an overview of Broken Infinity raises several questions. It seems that looking at the work plan in order to understand it as a design or a sign contradicts the need to physically walk in and around it, along the green path it delineates. The work, as its name indicates, is opposed to the concept of infinity it purports to convey. We have here an either/or situation – either we understand the sign from the work plan, or we experience it in the space as a broken sign. The viewers proceed in stages towards the complete picture and are forced to bend and push their way around entanglements of wooden beams. The physical contact at the point of interface between the two parts of the structure is also an obstruction that produces physical frustration. This point, which is also the site of the fissure in consciousness, lets in the concept of the sublime, which here creates a “negative pleasure” as a result of the structural tension between physical experience and conceptual perception. Gitlin creates a rupture of perception that accentuates this gap and this tension, and in fact thwarts the possibility of exceeding to the beyond. Broken Infinity is revealed as fertile ground for phenomenological uncertainty.